Thoughts on... The Promised Neverland, and Black Women in Manga

Every so often Shonen Jump provides us with a rare gem. This series, when it appears, will stand as a reminder of why the magazine is so legendary. I was introduced to Jump in secondary school, at the dawn of YouTube, back when Dattebayo's Naruto subs were regularly ripped and uploaded on the site without their permission (leading to their defiant withdrawal from the web). I quickly joined a small but committed community of pupils that circulated Naruto theories, engaged in Big Three debates, and read weekly scans on OneManga. I soon noticed a pattern, that the majority of my favourite series had the same logo on the back page. Naruto, Bleach, One Piece, Death Note, Shaman King, all carried the Shonen Jump seal. As the years progressed and my tastes diversified, I reconciled with the criticisms of Jump manga: formulaic, contrived, easy plots that were fixated with the Big Three, and yet despite the critics, I could always identify at least one series that challenged their theory: Hunter x Hunter, Assassination Classroom, and now recently, The Promised Neverland.

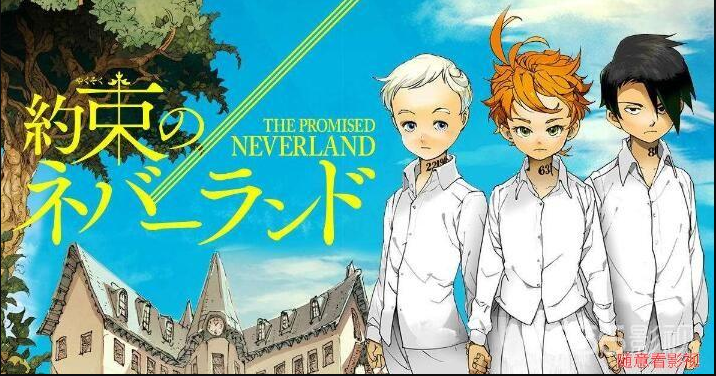

Our intrepid trio

The Promised Neverland by Kaiu Shirai is one of the freshest, most intriguing and unique stories to be published in Jump for a while. Set in the orphanage at Grace Field House, a group of children cared for by their "Mother", the kind Isabella, are nurtured until each of them are hopefully adopted by new parents. They are branded with numbers on their necks, and the only oddity is a series of arduous written exams they have to complete daily, their scores collated and ranked to determine the truly gifted children from the only-slightly gifted. Emma, Ray and Norman comprise the central trio, and their scores permanently dominate the top three positions. It is early established that the Grace Field children are not your average bunch, and their collective intellect proves vital during various parts of the story. That's the basic premise of the manga, but of course, there is a reason why they are in the orphanage, and a reason for the exams, the numbers on their necks, and the lack of adults. When the kids find out, their lives change forever.

Everything about it is interesting, from the child prodigy cast, to the innocent friendships, to the female protagonist who is not weak, nor any less intelligent than the males around her. Emma is a fantastic main character. She leads the pack, she encourages her friends, and her intelligence, wit and bravery are not anomalies to those around her. At times her character veers into the choppy waters of Nakamaland, but this can be easily assuaged by her age: just eleven years old and still a little idealistic. It's unusual to see a female protagonist of this nature in Shonen Jump; after all, it's a shonen magazine, and we've been given the impression that young men only want to read stories about other young men, but also, she totally contradicts the typical shonen females we have become accustomed to: overly sexualised like in Bleach, passive and sidelined like the kunoichi in Naruto, princessy, and if strong, then very quickly disarmed or disabled like the women of One Piece (compare the Robin we were introduced to in Alabasta with the silent Robin in Dressrosa, or the dichotomous nature of Amazon Lily-era Hancock and the heart-eyed mess during Marineford). There are of course women characters that break this trend, Anna from Shaman King is truly brilliant, for example, but have we ever seen a main character quite like Emma?

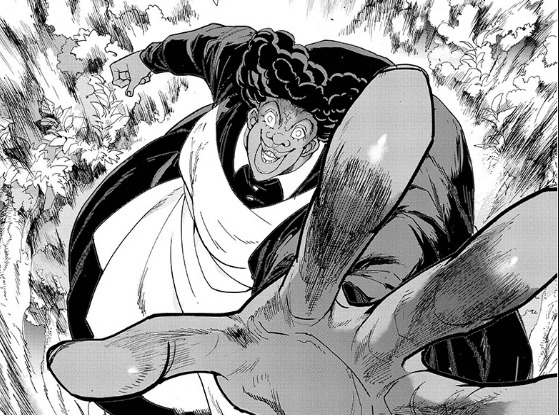

It was disappointing, therefore, to see such a trailblazing series fall into racialised tropes for another significant woman in the series, Sister Krone. I won't give too much away about the character, but Krone appears as one of the rare adults in the series who visits Grace Field House. She is also the only black woman. Her design is monstrous and alarming, and her appearances are often used for jump scares and shock value. Demizu Posuka, The Promised Neverland's artist, whilst talented, tends to reproduce racialised imagery for Krone's design: large clown nose, wide rubber lips, crescent eyes. Her body shape is considerably muscular and more masculine than Isabella, the more feminised white woman. Sister Krone is not in the manga for long, but her purpose is mainly to help the main cast progress through the plot: she scares them, she gets manipulated by her superiors, she has a change of heart and helps the children, and then she's gone. She never reaches her goal or realises her ambitions, and the children can only look back on her pityingly.

I mean...

I'll compare the panels below as an example. They depict pivotal moments in the manga where both Isabella and Krone frighten the children at different times. Unlike Krone, Isabella's ethnic features are not used to denote terror because they have not been so heavily emphasised in the first place. Krone's manic smile is made more frightening because of the flared nose, giant lips and wild crescent-shaped eyes. Interestingly, both women are given nonhuman expressions, but whereas Isabella is portrayed as emotionless and robotic, Krone is more animalistic--a common trope in the depiction of black villains.

Isabella. Chilling and creepy

...totally ridiculous.

I could go on, but I'll spare us.

I skimmed over her scenes because I just found them so offensive, and oftentimes, when the community engages in "women in manga" discussions, the portrayal of black women is forgotten, even though there is so much that could be said.

So I'll preface this by saying that I'm a black woman myself, so I'm not speaking as an interested spectator, but as someone from a minority group who has been confronted by distasteful representations of my femininity, beauty and worth in comparison to white European women by both men and women from various cultures. From Aunt Jemima and pickininny children, to golliwogs, and the treatment of Saartje Baartman, black women's right to womanhood has been challenged, withdrawn and attested. This treatment is the reason behind Sojourner Truth's question, "ain't I a woman?", Audre Lorde's constant struggle with mainstream feminism, and for Althea Jones-Lecointe's explosive protests on the streets of London. We are seen as masculine enough to withstand abuse, too aggressive for sympathy and framed as the dark contrast to white femininity. The same features we are berated about (lips, eyes and nose) are only beautiful on women who are nonblack. In the west, patriarchy dictates that white women are precious and in need of protection, it's why they are often depicted as damsels, and this depiction has real-life implications for crime reporting in the news. For further reading, google papers about "ideal victim status", check out the work of Elliott and Quinn, or read Ida B. Well's Southern Horrors. Black women are rarely victims, instead we are masculinised, and our media portrayals reflect this ideology.

These western ideals are harmful and ubiquitous enough that they infect societies as remote and as insular as Japan and other parts of South East Asia (after all, at one point, the "sun never set" on the British Empire, and European colonialist beliefs on race and superiority had an influence on pretty much every continent in the world). You can see examples of this on YouTube videos from channels focused on Asian culture. South East Asian communities will typically be asked for their opinions on western pop culture and trends. Just observe, on any video relating to black people and "Africans", how often the participants express negative descriptors of black people: black people are poor, they play basketball, they aren't as smart as white people, they are gangsters, they are ghetto, the women all wear fake hair, they engage in violent crime. When activists say "representation matters", they are not just reciting a catchphrase, but shedding light on the harm that comes from unfair representations of nonwhite people.

Hmm. Looks familiar.

Representation is bigger than just putting more black people on screen; it is about normalising blackness, allowing for black people to be represented in the same nuanced, interesting and diverse scenarios as white people are. How peculiar that the same insular Asian communities are able to portray white people positively, but are prone to fall onto distasteful stereotypes for black people. Take a look at shojo manga, and at how many of those series involve "half-Japanese" noble boys who are heirs to some dynasty in England, or how often Britishness in particular is used to denote high class, the aristocracy, and wealth. Mangaka are getting these assumptions from somewhere.

Sister Krone's design reignited issues I had with other characters in the past: Jynx from Pokemon, Dragon Ball Z's Popo, and Killer Bee from Naruto, the only significant black character and the only one who has to rap every other line. Shaman King, whilst I love that manga to bits, also gave us Chocolove, the afro-wearing, rubber-lipped shaman who just so happened to have a jungle-based guardian ghost. These series are equally interesting in their lack of black women, despite there being a myriad of white-appearing ones.

HMM. LOOKS FAMILIAR.

I just think Chocolove deserves better

Although things look bleak, there are some saving graces. Thank God for Tite Kubo, who gave us the human-looking Yoruichi and the complex and tragic Tosen, two black characters, female and male respectively, who were not signified by the oddity of their blackness, but simply had brown skin, cool powers, and interesting backstories. Likewise Berserk, whilst technically a seinen, gave us the wonderful Casca, the only strong, female soldier in a medieval setting, and once again, her skin colour is not used against her, or represented in an unflattering way, she just so happens to be a black woman in a white man's world. I have to give mention to lovely Canary, our quiet and powerful fighter in Hunter x Hunter, who is an interesting character and is not caricatured in any way. There are plenty more black characters out there that stray away from minstrel-inspired designs, but when I do see them, I often wonder how the mangaka who drew them were able to divert from an ideological barrier that clearly influences so many masters in the field. Such a mangaka would have to have read widely, done enough research, engaged with diverse western media and have had conversations or friendships with black people. Of course it takes effort, but effort and artistry share a long and beautiful marriage.

Yoruichi. She's so cool.

Canary. What a cutie.

I wanted to express my feelings on this because unsurprisingly, The Promised Neverland's popularity continues to grow, and with the announcement of a January 2019 anime, more animanga fans will be introduced to the series. And just like we've seen so far with the discussions and thinkpieces regarding it, there will be a lot of praise and admiration for Emma, a lot of people championing the series as a landmark example of strong and positive womanhood in manga, and they will almost certainly forget Sister Krone, or even worse, see nothing wrong with her portrayal at all. I can predict there will be plenty of excuses made, the old favourite about Japanese Culture will be said at some point, and a few accusations of snowflakes and SJWs will be hurled at the few who do take issue with her depiction. Regardless, we should not shy away from critiquing art, and from challenging negative aspects of stories that we like. Art is there to be interrogated, and no artist is infallible.

So of course, continue to praise Emma. She's a fantastic protagonist and a breath of fresh air in an industry that often portrays women as two-dimensional and inferior. But as you do, please save a thought for Sister Krone.