In Defence of Chainsaw Man

We’re moving into a new anime season and the autumn hypefest is over. Chainsaw Man, one of last season’s most highly anticipated anime, completed its first run with a lot of success. It’s garnered new fans, the subreddits are growing steadily, and the fanart has flourished. A lot of attention was paid to MAPPA’s adaptation, which was handled with much care and artistry. But Chainsaw Man is not without its detractors.

It’s something I was wary of. After the first PV dropped last year, the rumblings of an excessive hype started. In the weeks leading up to its October launch, it was clear we had ventured into unsatisfiable waters, and as expected, criticisms emerged. As I browsed through comments, I saw common threads: people felt there was a lack of worldbuilding, they disliked the relatively slow pace, they were unsure about the power systems, how devils worked, and what impact the setting had on wider society; they wanted more from Denji, and they expected a proper establishment of the heroes, villains, and antagonists. I don’t think any of these are unreasonable, because for the most part, anime-onlies were miss-sold by manga readers.

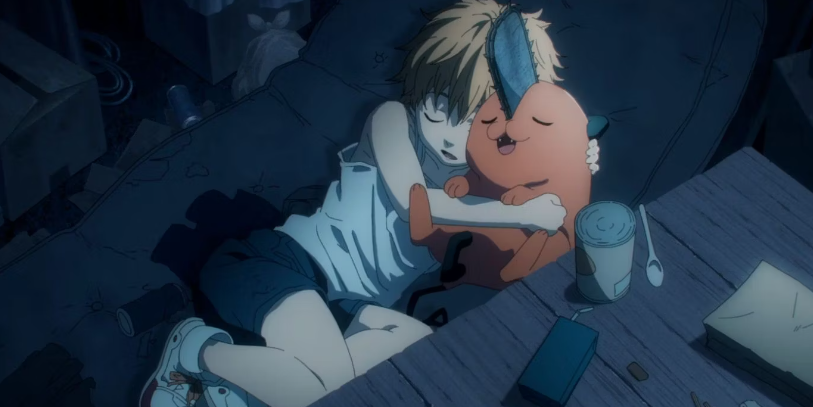

2 dummies 1 misanthrope. Fantastic opening btw.

If I had never read Chainsaw Man, I would have started the anime expecting it to be a darker Jujutsu Kaisen, with One Piece or MHA style world-building, Attack on Titan-level mystery and twists, Berserk violence, and a type of existential philosophising as seen in Neon Genesis Evangelion. Why? Because leading up to the October launch, manga readers banged on about how “shocking” Chainsaw Man is, how it’s unlike anything Shonen Jump, or dare I say, any shonen magazine has produced till now, that it’s a “seinen dressed up as a shonen”, a story for the real savants of mangacraft. I observed manga-readers promoting Chainsaw Man to potential new fans, and I was a little disappointed that the story was being so misunderstood.

Just a broke boi tryna get through life

Chainsaw Man is different from the current popular shonen reads. Denji is unlike Eren, Ichigo, Luffy, Yuji, Natsu, Naruto, Tanjiro, and Izuku. He isn’t trying to avenge a brutally-murdered family member, nor is he on a quest to realise a mentor’s legacy, or achieve a noble goal that would earn him respect and admiration for the next generation. His father is irredeemable and their relationship is barely touched on. His life is unfair and he accepts it totally, caught up in never-ending debt and left to the mercy of the yakuza. Denji doesn’t contemplate the cruel mechanics of capitalism and vows to overthrow it—he just lives, day by day, and gets what he can from it. When he joins Public Safety, his main goals include having a warm place to sleep, nice food, kissing girls, touching boobs, going on a date with Makima, and having sex. That’s it.

By contrast, Aki is the brooding, contemplative character that we’ve become accustomed to by now. He fits the Sasuke-Uryu-Shoto-Gray-Urie archetype, but as a detraction from that model, he isn’t Denji’s rival. He may vie for Makima’s attention, but his journey and goal have nothing to do with Denji: he doesn’t look at Denji and wonder why he’s grown so quickly or achieved so much—partly because Denji never worked for his powers—but mainly because Aki’s goal is different. He’s on a revenge quest. They’re colleagues, not friends.

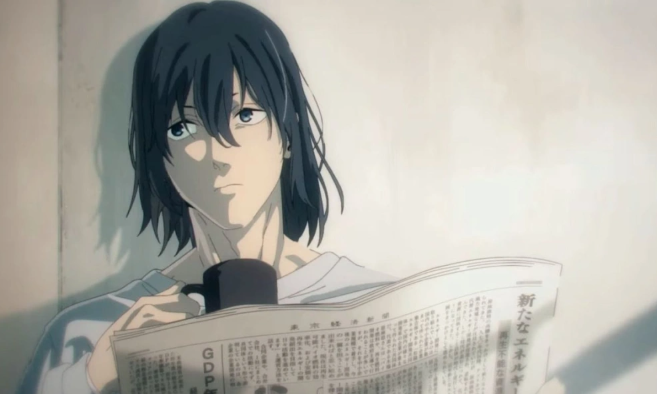

This morning routine sequence almost, ALMOST beat Rin’s from Free! which is a personal fave of mine. Almost.

Also straying from convention, Power isn’t the sensible but neglected female to balance the two male leads. At her core she’s a villain, a fiend actively working against humanity, but dragged into Public Safety against her will. She’s just trying to survive, to do what she’s told so she’s not exterminated. And she is an impulsive wildcard, and violent, and not serious at all, and has a superiority complex. Once again, her story, and her aims, are isolated from Aki and Denji.

With three protagonists all siloed into their own worlds, and an extended cast that is equally isolated, with most of their motives either unremarkable (like Kobeni) or undefined (like Kishibe), it almost feels like you’re reading multiple stories at once. But these stories slowly converge, and the process is subtle, like when Aki joins Denji in assaulting Katana Man, or when Himeno makes a pact with Denji on her balcony, or when Denji and Power unite to defeat Kishibe, or when Denji fights the Bat Devil to save Power, or when Kishibe admits to getting attached to his new charges, or when Denji witnesses Aki crying, and then contemplates his own humanity. Slowly, the characters become aware of each other, and the walls between them are broken. In my opinion, this is what makes Chainsaw Man special.

On the other hand, they’re all crazy.

The shocking moments are uncommon, but memorable, and it’s the impact of these shocks that drives much of the hype surrounding the series. This is what people were using to generate the high expectations for the anime and was typified in comment sections across the internet in the wake of Episode 9, where manga readers promised anime-onlies that this is where the story REALLY begins, as if the episodes before were mere padding, or just a means to all the shooting and body combusting. When some Chainsaw Man fans recommend the series to newbies, they are clearly thinking about Power, Aki, the Darkness Devil, Reze, Angel, and Quanxi, and the huge twists in their stories. But the shocks and twists don’t make the story. The characters do.

There is a type of manga reader who takes themselves really seriously once they’ve read certain Key Series. They began their manga journey associating shonen with series such as Naruto and One Piece, and then moved onto Attack on Titan, where the frequency of brutal deaths and complex mystery made them reduce the former series they loved to childish nonsense, and ascribe anything dark and complex as “seinen” or “not like that other shonen”. Such a person inevitably transitions to Berserk, Vagabond, and Vinland Saga, and then becomes elitist in how they navigate and measure the quality of certain shonen, the metrics typically being: how dark, how shocking, how violent, how realistic. Chainsaw Man became the latest Special Thing in these circles, and the quiet beauty of the story got lost in the hype.

For only the most serioustest of manga fans (no shade, I like all 3 btw).

So I understand completely if some anime-watchers found the show underwhelming, and are still wondering what the furore was all about—I just think you were given the wrong impression. Chainsaw Man isn’t a story that you can easily power scale, or compare characters on morals and merit; there’s no clearly-defined system in place, and the world is explored in sketches. Morality is generally ambiguous, but there are obvious villains, even if they have understandable motives. Mostly, the characters are dubious, but compelling in how they relate to each other, and these conflicting morals interact in a myriad of realistic, if not devastating, ways.

I’m a huge fan of the series. It is monotonously exciting, with meaningful sequences that unravel during daily mundanity, and I want more people to read it. If you were disappointed by the anime, I would encourage you to try the manga. The story still might not be to your liking, but at least you have a clearer impression of what it’s about.

I am hyped to see her next season, though!

It’s important to go into any series with realistic expectations, because nothing could have lived up to the misguided hype that Chainsaw Man endured, and we’ve all witnessed many exceptional manga series wane in popularity because of overblown fan frenzy. Let’s give Fujimoto a chance to draw readers in with his effortless talent, because he really is a brilliant author who deserves all the success that’s come his way.