The Flowers of Evil (Manga Review, spoilers)

This was a difficult read. Initially, I dropped it out of frustration. I read Happiness by the same author years ago, and was touched by its fragile narrative, and its quiet but purposeful study of the characters. In Happiness, Shuzo Oshimi provides an array of ordinary people faced with complicated and intense tragedies, and whilst the ending is subtle and conservative, it holds a heavy significance. By contrast, events move quickly in Flowers, unrealistically so, and character developments jump from one extreme to another within single chapters, so that by the end of a section of dialogue or scene, I feel like I’ve run an incoherent marathon and had the finishing line snatched away just at the moment of conclusive relief.

Then, an essay penned by Oshimi appeared on my For You Page. Taken from the afterword of another series, Okaeri, Alice, it details the author’s struggle with sexuality and gender identity. Four very upsetting pages, very raw and refreshingly honest. If read by eyes that are keen to misunderstand minoritised genders, the essay could be taken as something obscene, problematic and frightening, and so I was doubly touched that Oshimi still shared their thoughts with the world, opening themselves to scrutiny and questioning. There’s no need for me to quote it, but someone has provided a link to it in this thread. It’s worth the read, and it recontexualised Oshimi’s work, including the equally upsetting Blood on the Tracks. The essay made me give Flowers another chance, and I decided to read the manga as an allegory, where the characters become archetypes, literary devices to explore a decayed mental effluence—of Oshimi, the reader, and the characters themselves. Sometimes it does help to enjoin the artist and the art.

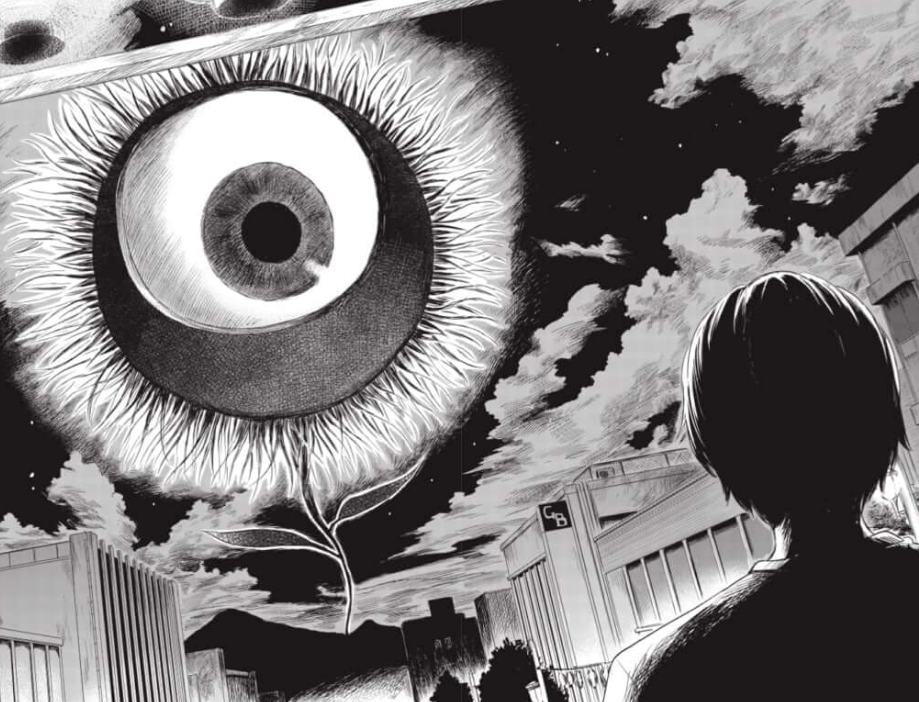

The beginning of destruction. Here were see the outline of the flower that runs as a motif throughout the story.

In Flowers of Evil, introvert teenager Takao Kasuga steals the underwear of the girl he fancies, Nanako Saeki, from her gym bag. This action is witnessed by the classroom oddity, Sawa Nakamura, who later confronts Kasuga—not to chastise him, but to force him into a contract as a “fellow pervert”, where she cajoles him to commit increasingly destructive acts so they can both make it to “the other side”. The story is set in a droll country town, and I’m once again intrigued by this side of Japanese social commentary. Just going by other series I’ve read and loved—The Summer Hikaru Died, Boys of the Abyss, Goodnight Punpun—there is a running theme of helplessness and imprisonment that pervades these small towns, and in The Flowers of Evil, Nakamura is desperate to escape what she sees as a boring and lifeless existence, caused by the setting itself. Her wish to reach “the other side” resonates with Kasuga, a boy of deep, sensitive intellect, as denoted by his pastime of reading classic books, his favourite of which is Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil) by Charles Baudelaire.

Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal is an intriguing collection of poetry. Seen as controversial for its time, the poems consider mortality, grief, Parisian culture, sexual desire, and more. Much attention is given to female sexuality and the allure of feminine eroticism, with the poet observing these themes from a vantage point in some instances, and a yearning participant in others. Throughout Flowers of Evil, I could see Kasuga mirroring the poetic observer, trapped between the various women in his life, oscillating between infatuation, obsessive admiration, and abject fear of the power they yeild, a power that he is weak to. Each of the women play particular roles in Kasuga’s life, abating or exacerbating his internal decadence.

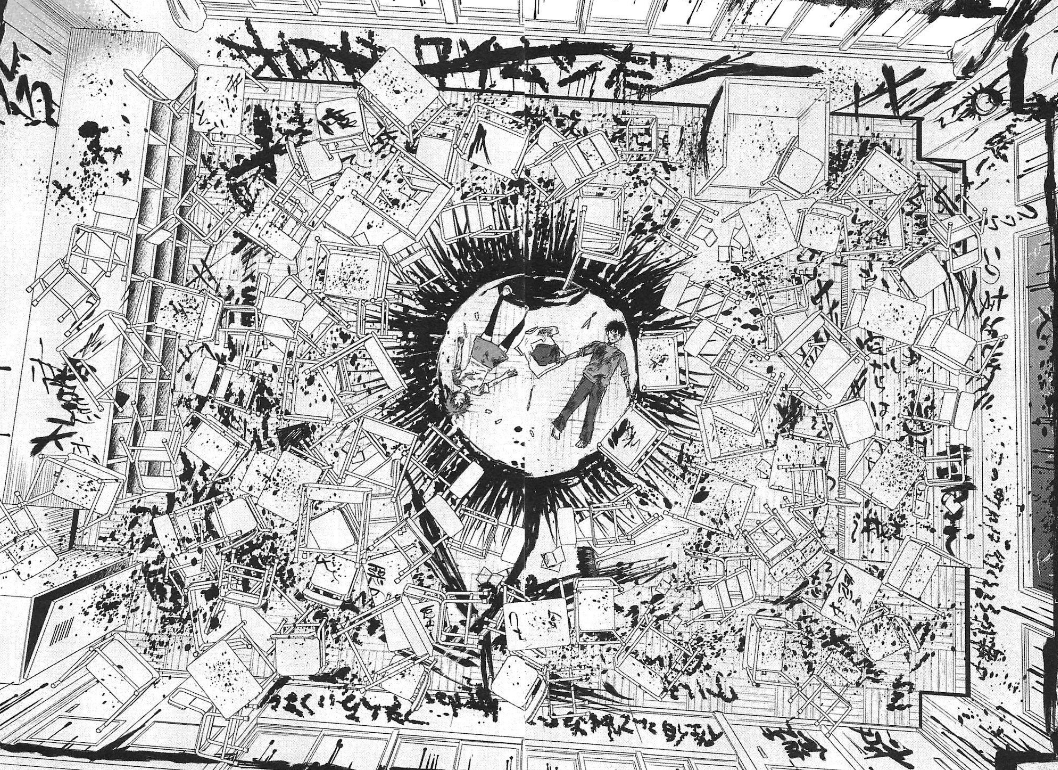

Best visualisation of being caught between a rock and a hard place.

The relationship between Kasuga and gender anxiety is apparent throughout the story. He is confronted with various states of masculinity and femininity and he struggles with the two. We have the hyperfeminine Saeki, who uses her apparent magnanimity to shield her sadism; Nakamura, openly aggressive; Kasuga’s mother, pensive and sensitive, and then there’s Tokiwa the healthy all-rounder, albeit bearing an unsettling resemblance to Nakamura. The men are less developed, and I believe this is intentional. Kasuga’s and Nakamura’s fathers greatly resemble Seiichi’s father from Blood on the Tracks: they are passive and directionless and both are eventually assaulted and overpowered by Sawa Nakamura. As the story progresses, Mr Kasuga becomes an alcoholic and contributes very little to his household. Takao Kasuga collects two friendship groups in the respective schools he attends; a band of nerdy, sex-obsessed boys, totally interchangeable and forgettable. Finally, Tokiwa’s boyfriend is the typical chauvinistic abuser; he’s controlling and insecure, and uses his hypermasculinity to control his friendship group. Throughout it all, Kasuga shares elements of all these personalities within him, and delicately traverses a spectrum unique to himself.

The characters are cruel to Kasuga, and he suffers various forms of punishment throughout the story, as if he is paying penance for his own insecurities. The worst comes from Saeki. She admits to being drawn to Kasuga because he accepts her imperfections, and he makes her feel safe and ordinary. The sinister, conceited undercurrent of this desire becomes clear when Kasuga rejects her for Nakamura. Unable to accept that someone of his stature has no interest in her when everyone else does, Saeki becomes obsessed. She stalks Kasuga until she finds his secret hideout, and then rapes him when he refuses to kiss her. Afterwards, she burns the hideout, permanently destroying his refuge. Chapters later, Nakamura sexually assaults him also, shredding the skin on his chest after forcing him to undress. This exemplifies the nadir of their relationship, after which they make their final pact: an act of suicide before horrified onlookers at the town’s summer festival.

A startling observation in Oshimi’s personal essay contends with their inner woman bleeding with the trauma of cisheterosexual intercourse. Oshimi discusses their own interpretation of “the other side”, stating that it is “where pleasure ends” and their inner self and outer body become one. They conclude that “the other side” can’t exist unless through death or suicide, so the only solution is to create one for themselves. In one visceral moment during Nakamura and Kasuga’s suicide pledge, Nakamura tearfully confesses that something within her has been crying for liberation. She then asks him, “where is the exit … where’s the other side … There’s no other side…there’s nothing”. Nakamura, a character that long precedes the cast of Okaeri, Alice, vocalises Oshimi’s own internal struggle in the present.

Before the festival….Nakamura doing what she does best: making a mess and beating people up.

On the fated day, both teens douse themselves in gasoline upon the performance stage, but Nakamura pushes Kasuga away just before clicking the lighter. In distress, Kasuga looks on from the crowd, but the catastrophe is averted when Nakamura’s father saves her just in time. Years pass and Kasuga, Nakamura, and Saeki move away to different towns. Kasuga is plagued with confusion about Nakamura’s final act of mercy, unable to understand why she chose to reach “the other side” alone. He struggles as a recluse through high school, and finds solace in Tokiwa who, like Saeki, realises her true self when she’s with him, but unlike Saeki, Tokiwa is honest, and they share a mutually affectionate relationship. Kasuga saves Tokiwa from her her self-doubt, and Tokiwa saves Kasuga by helping him confront his past.

Another running theme in Les Fleurs is loss. In Flowers, Oshimi explores the loss of sanity in the relationship between the three protagonists, of life, and innocence, how a soft-spoken schoolboy is dragged from his benign existence and thrown into a world of extremes, how a sweetly adolescent crush can turn obscene and abusive. It also considers the loss of trust, how a kindly Saeki could become so cruel, and even when Kasuga meets her when they are older, she is equally bitter, and her words almost send him into a relapse.

On the cover of Kasuga’s edition of Les Fleurs is a wilting flower that often follows him on the page during times of his distress. Sometimes the flower opens to reveal an ever-watchful, judgemental eye. It’s an omen, a visual representation of his decaying mental state, and it prevents him from progressing. The moment he finally pulverises the flower is when he musters the courage to confess to Tokiwa, but it returns as a stain on his palm: he has not confronted his past, nor has he told her the truth of his traumatic experience in his old town. With Tokiwa’s encouragement, they track down Nakamura and visit her together. Kasuga and Nakamura’s seaside reunion is awkward and stilted, and Nakamura finally turns to leave without properly explaining herself. Not wanting her to abandon him again, Kasuga wrestles her to the ground in front of a bewildered Tokiwa, and then he drags Tokiwa into the affray. Soon, the trio is splashing in the sea and laughing. A group baptism.

The chapter of this meeting is both satisfying and relieving; at last, both troubled teens have resolved their issues and are in a better place. And now, Kasuga can live healthily with Tokiwa, having confronted the past with a companion.

The cleansing sea.

At several points in the story, I was worried this was leading to a devastating end, and every time Kasuga had some development or progress, I imagined everything crumbling in the following chapter. But the story after the failed suicide is slower and more meaningful, and we observe a careful unravelling and rebuilding of Kasuga and his family. In a heartlifting moment, we are shown a montage of everyone as adults, starting new families, reuniting with old friends, moving on from their childhoods. It’s a palate cleanser from all the trauma.

The final chapter reveals the world from the perspective of middle-schooler Sawa Nakamura. Quite clearly suffering from some psychotic illness, everything is dark, covered in flies, and people are mere smudges and shadows around her. The abrasive way she speaks to everyone is her coping mechanism against frightening surroundings. Overwhelmed, she hides beneath her school desk for reprieve, and sees a shadow slip into the classroom. Only when the shadow crouches towards a fallen gym bag and sniffs the underwear inside does the face of Takao Kasuga appear. It’s the first time she sees another human face.

The disturbing reality of Sawa Nakamura.

I’m so glad I gave this another chance. I’ll be honest and say the first half definitely has pacing issues, and whilst the characters felt like allegorical devices in the beginning, by the time of the summer festival and onwards, everything is much more fleshed out and meaningful. There are truly devastating moments in this story, but it is all beautifully written. The concept of truth as healing is a profound one, and it is inspiring to see Kasuga re-discover himself by being honest with who he is, not running from the past, but using those experiences as learning moments. Most importantly, we see how his romantic relationship helps him along the way. His situation with Nakamura was exacerbated by its isolation. Tokiwa provided community.

This is a hard manga to rate. For the first half, I can only give a 6.5, but the second half is a straight 9/10. I’m still pondering the messages, and reading through Baudelaire, linking the themes of death, loss, rebirth, and sexuality with passages in the manga. It reads more like a play than a graphic novel, which makes for an intimate and confrontational experience. But I definitely recommend you read it.