Eden: It's an Endless World! (manga review, spoilers)

Eden: It’s an Endless World! Is a thought-provoking post-apocalyptic seinen manga by Hiroki Endo. Set during the outbreak of the deadly Closure Virus, the story chronicles the lives of various communities as they grapple with political, environmental, and social conflicts directly related to the pandemic. The story spans vast distances and generations. At first, we follow Ennoia and Hannah, two teens left alone on a Caribbean island with the doctor who once worked with their government-affiliated parents, and a powerful AI robot, Cherubim. After Dr Lane’s death from the virus, Ennoia and Hannah leave the island and have children, one being Elijah, the protagonist. Elijah undergoes several transformations as the story progresses: from a sensitive yet shrewd lone traveller, to a precocious teenager, to a major player in a global cartel, to a mercenary, to a depressed drug addict, and finally ends the story as a survivor, sober yet traumatised from all what transpired over the course of his life.

Although I don’t read a lot of post-apocalyptic fiction, Eden is the most unique out of those I know. I appreciate how Endo properly encapsulates the global aspect of the pandemic by exploring the ways poverty, conflict, and crime affect different parts of the world. Various African countries suffer from civil war and refugee crises, indigenous Asian communities find themselves oppressed and on the verge of ethnic cleansing, South America is plagued by drug cartels and gangs, heavily funded by westerners – Ennoia being the most infamous and powerful. All the while, a major world government tries to dominate the political landscape by crafting its own new world order: Propatria pressures less powerful nations to join its ranks whilst violently subduing communities that want to stay independent – colloquially known as Nomads.

Propatria is influenced by gnostic beliefs, where those who join its federation are deemed to have ‘gnosia’, or wisdom, and those outside the union are still in ignorance, ‘agnosia’. The federation believes the current world is incomplete, and they strive to create a new, complete world that exists outside of god’s ‘insanity’. There are various ethnic inequalities within Propatria, as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia are the leading powers within it, which naturally means far-right Christianity is appeased in order to maintain the federation. Various Muslim communities are oppressed, and we follow the lives of some Islamic activists as they fight for their autonomy.

Alongside this complex political landscape, the Closure Virus returns as the Disclosure Virus – a more violent iteration of its predecessor, and more supernatural in its progression. As people die from the virus, their bodies explode into crystal statues called Colloids that can communicate even after death, and these statues then evolve into large structures that contain the living data of every person on the planet who has succumbed to the virus. As the global landscape becomes bleaker, humans begin to voluntarily relinquish their bodies to the Colloids in order to leave the world behind and enjoy some peaceful existence as living data. The Colloids are enticing, and at various moments, we see characters turn their backs on earth to assume a tranquil, yet unconscious afterlife, and other characters, whilst tempted, turn away from the Colloids and try to make the best of the world in which they exist.

There are so many philosophical and religious threads to Eden, and these moments make you consider what you would do if you were in the same situation. We already see similar behaviours now. I spent my formative years in the Christian church, and people of my generation got older, saw the state of the world, and wondered how the church was going to respond to it. When the church leaders instead directed us towards heaven, declaring that the bible predicts things will only get worse until the Second Coming, we would retort: ‘the church is so heavenly-minded that it’s no earthly good’, meaning that the concept of heaven, whilst a comfort during hard times, can also send people into a state of slumber, or used as a defence mechanism against inexplicable horror. The humans of Eden who enter the Colloid have relinquished their responsibility to their planet and community, and embattled by hardship, have chosen personal peace. Endo refrains from criticising such actions, but allows the story to explore a realistic, human response to tragedy.

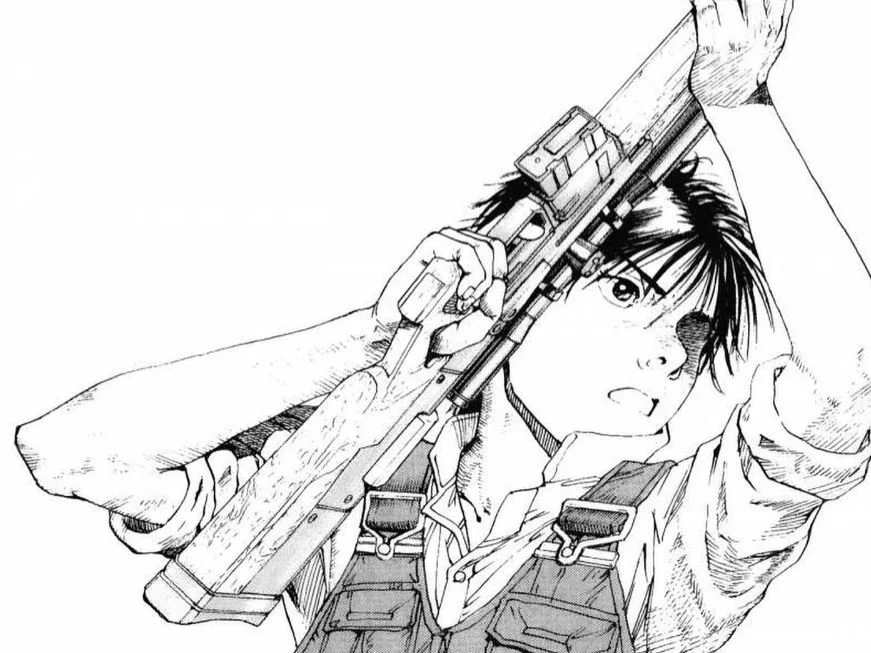

Elijah…he goes through a lot.

Elijah, as a protagonist, undergoes so many metamorphoses that it’s hard to pinpoint who he is. The environment forces him to perform various functions: when he is taken hostage by Nomads, he must comply for his own protection and for the safety of Cherubim. When he is thrust into an inter-factional conflict in which his younger sister is captured by Propatria, he must assume the role of freedom fighter and tactician to save her. Afterwards, he lives in a brothel and finds himself in the crossfires of gang warfare, which moulds him into a merciless killing machine. He begins a relationship with Helena, who is eventually killed by agents of Propatria, which begins a lengthy conflict fuelled by vengeance. Lastly, he undergoes his biggest task yet: reclaiming his sister after her years in captivity, but just as she is finally about to reach safety, she is killed, which plunges Elijah into a season of despair. His solitary confinement as a drug addicted wraith is likely the first time since his childhood that he has had to contend with himself and his own identity.

Elijah has a complex relationship with Ennoia, who for most of the story remains a shadowy, stoic drug lord, but at the end, we see his compassion and dedication to his wife. Ennoia’s final mission is to visit Hannah just as she returns to their childhood island to join the massive Colloid structure there, and on the way, his two most loyal friends willingly sacrifice themselves in violent gun fights with Propatria to ensure he reaches his destination. Happening simultaneously with the island battle is an incoming cosmic disaster, as what appears to effectively be a wormhole makes its way towards earth, and Propatria, forced to reform as a new global alliance, utilises the skill of an international team of scientists to develop countermeasures that will alleviate the worst of the inevitable devastation.

The members of the former Propatria who still believe in a separate, complete world elsewhere, join with the Colloid in the hopes it would hasten earth’s destruction. It is revealed that a small number of humans, Ennoia being one of them, have antibodies that make them immune to the Disclosure Virus. This would allow Ennoia to maintain his sense of self in and outside the Colloid, effectively making him a god. Using this ability, Ennoia relives his childhood memories with Hannah, but the memories are incomplete and he realises the Colloid is simply an illusion that cannot recreate real life. He rejects the Colloid and dies alone on his own terms, whereas his rival, a member of Propatria who is also immune, assimilates with the Colloid. His plans are thwarted by Sophia, the surprise final possessor of the immunity, and she subdues the Colloid’s power whilst sacrificing herself all to save her friends on earth – an action that the previous Sophia, who abandoned her eight children and tried to kill another, would never have done.

Eden is a carefully crafted story and it’s not an easy read. Alongside these philosophical themes is a lot of heavy science exposition. Endo could have skirted over these moments, but he actively includes all the debates between scientists as they plan a course of action to save the world. These moments, whilst difficult to follow at times, are meaningful in that they provide another stance that counters, as well as complements, the religious and cultural views already explored. There is also a lot of violence. Many people die throughout the story and Endo does not shy away from the realities of war and conflict.

Some of the death scenes are repetitively traumatic: there are two side characters that we follow at different parts of the story. One is a doctor who has already lost his wife and receives Colloid-induced visions from her inviting him to join her inside. After losing his colleague to the Colloid, the doctor is tempted, but opts to begin a relationship with his assistant instead. After almost losing his life during a mission to get supplies from a Muslim commune, the doctor returns to his own village only to discover the same insurgents have desecrated the community there, including his new love. Numb with grief, the doctor journeys to the Colloid, but then he glances back at his village behind him, and he chooses to rebuild. The same thing happens to a young boy who, whilst helping the protagonists cross through Propatria-infested terrain, sees his sister and mother shot dead in front of his eyes. Once again, the boy rejects the temptation from the Colloid and tries to live again. These scenes are difficult to process, but necessary in delivering the message of perseverance against an “endless world”. With all this death, it’s hard to stay too attached to any one character because sooner or later, they will die. This adds constant moments of tension that make for a visceral reading experience.

As an aside, I wanted to mention something else about my reading experience. Recently, there have been increasing reports about the relationship between Generation Z and modern media. Apparently, zoomers are emphatically rejecting sexual scenes in the content they consume. These reports have been met with exaggerative panic among millennials, who for some reason have interpreted this coy sexual aversion as some christo-fascist puritanism. Millennials are annoying like that. I personally always took the news with mild bemusement. Perhaps, a generation bombarded with constant social media pressures, unrealistic beauty expectations, hypersexual content creation, and unparalleled access to pornography has become a little squeamish? It’s not rocket science. I am not so heavily invested in the lives of young people that I feel the need to panic about their sexual jitters. A bit of maturity will help them to strike a healthy balance as they get older, and perhaps a more sex positive, rather than sex obsessed, media will level the playing field a bit.

However, I struggled to find healthy and mature discussions about Eden online because of the abundance of repetitive complaints about the sex. Any time a chapter features a sex scene, there will be several comments expressing exhaustion, or questions about its relevance to the plot, or incensed declarations about dropping the manga altogether. It was bizarre and consistent, and I do find these complaints concerning. It’s a coming-of-age story about a young man learning the ways of a cruel world. Sexual experimentation is part of that. The world of Eden is unconventional, with many societies experiencing moral breakdowns or grey areas, so whilst not ideal, it’s not surprising to see said young man – who has been actively killing and partially running an international drug cartel – having sex with women several years his senior. There is no need for the author to add a disclaimer in the notes about how wrong this is. These issues are part of the story and build the tapestry of the setting. I would understand the complaints more if there was awkwardly inserted, gratuitous scenes without any character or romantic build up, of if author followed the route of many others and threw in rape after graphic rape (with titillating angles of the women victims) just to show how evil men are, but Eden isn’t like this at all. The sexual content is coherent with the rest of the plot.

At 126 chapters, Eden is a relatively short, but uneasy read. It requires commitment that is incongruent with binge reading, but the story is rewarding nonetheless. This was written in the late 1990s, where the world was no stranger to global disasters, but reading this after the Covid 19 pandemic, and during the current genocides happening in Sudan, Palestine, and Congo, as well as the oppression of the Uyghurs in China (all of which feature in the story), Eden has carved itself as a saliently relevant story. It is a timeless but criminally underrated series, and I’m truly thankful to the kind twitter mutual who recommended I read it several years ago. I finally got there in the end, and I’m glad to have read it.

9/10