Tanabata Country (Tanabata no Kuni) Review - Spoilers

This is an unusual seinen manga written and illustrated by Hitoshi Iwaaki that I think deserves more attention from Western fans. Considering Iwaaki’s other extremely famous series, Parasyte, Tanabata is relatively obscure. At four volumes, it makes for a great weekend read, and although the manga is short, it will remain with you for quite some time. Like with Parasyte, Iwaaki explores the subjectivity of morality, the upending of social norms, and the notions of what makes someone truly human through this tale of unidentified alien life forms meddling with earth’s affairs.

We follow Nanmaru, a university student who possesses the strange ability to create holes in random surfaces by willpower. He receives a note from professor Masaharu Marukami to attend an office meeting, only to discover that the professor has been missing for several days since visiting the isolated Marukami Village. According to his students, Nanmaru and Marumaki-sensei share the same ancestry. The answers to Nanmaru’s powers, and Masaharu’s disappearance, will be found in the village. Upon reaching, the students discover that the villagers are eerily elusive and private, hostile to outsiders, and extremely protective of the mountain range that borders the town. A small number of villagers can use the same power as Nanmaru, albeit at a more advanced level, and they are known as the ones who can reach “beyond the window”.

Nanmaru’s power turns out to be quite dangerous. Not only does its repeated use slowly transform the user into an alien-like creature, “reaching beyond the window” means he can vaporise people and objects to another dimension. Some villagers possess the power to look beyond the window, and they are terrified by what they see there. When a village defector starts murdering people throughout wider Japan using the power, Nanmaru is forced to intervene in order to save the villagers and the world at large.

There’s a lot of ugly things in this manga.

The key point of contention is the ideology of Marukami Village. For most of the story, we are left pondering the horror of the world beyond the windows, as the villagers’ fear is visceral enough to leap from the page. At a pivotal moment, Marukami resident Sachiko finally describes what she sees: a desolation, a space where nothing exists, a dark unknown that is terrifying in its opaqueness. I was stunned and slightly underwhelmed by this revelation, but after a moment’s thought, everything started to make sense.

In essence, the villagers’ behaviour is irrational: they’re in possession of a world-changing power but do nothing with it, they never leave the village, they don’t socialise with anyone, they venerate the mountain, and they habitually perform a yearly festival on the mountain’s peak in an attempt to communicate with their extraterrestrial forebears even though they haven’t received a visit for over a thousand years. They maintain this arduous lifestyle because they are frightened of the nothingness that exists outside of it. This is so reflective of religious (and political) beliefs in general: there must be a reason for everything, otherwise the truth that so much suffering and pain just happens by chance and circumstance would be too depressing to bear. People may doubt their faith or question the necessity for their own rituals, but they perform them anyway in the hopes that it will all make sense one day, and that their behaviour is connected to a higher purpose. Desperate to avoid the abyssal darkness that they can see beyond the window, the Marukami villagers venerate their leaders who can reach to the other side, hoping that at some point, their lives will have meaning.

Nanmaru’s intervention is vital here. Having not been brought up in the village and only recently made aware of his heritage, the villagers’ customs and rituals make no sense to him. He spends most of the story trying to find a way to use his powers for employment or to help others, and it baffles him that Marukami Village has had full knowledge of this gift for over a thousand years and have done nothing with it other than protect a mountain. Simultaneously, Yoriyuki the defector leaves the village once he realises the culture of fear has become a chain around their necks, preventing them from seeing anything beyond the mountain range. His acts of violent rebellion are to jolt the villagers into action, to make them do something, anything, different from their norm. His final act – creating a massive sphere to spirit himself to the other side of the window – is as much a cry for help as it is a protest.

To the window with you!

Iwaaki does an excellent job in portraying the villagers, as their behaviour made me intensely frustrated during reading. Every reasonable question Nanmaru asks is met with shifting gazes, apprehension, and half-formed sentences, as they refuse to reveal the truths of their village due to their unwavering loyalty to literally nothing. Nanmaru is an interesting character in that he’s endearing, naïve, and viewed in low regard by his fellow students who all seem to think he’s an idiot – and sometimes, their assessment is accurate. However, his frank, simplistic way of looking at the world confronts the convoluted beliefs of Marukami Village, and in his plain tongue, they are forced to accept that their culture doesn’t make much sense. Alongside these frustrations is a feeling of deep isolation. There is a strong sense of suffocation and claustrophobia that accompanies the reading of Tanabata, due to the secretive and suspicious nature of the village.

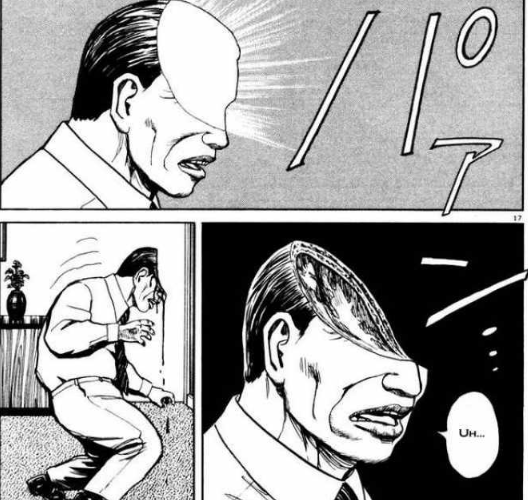

There is plenty of gore in Tanabata, which would come as no surprise if you’ve read Iwaaki’s other works. The face reveals of those who have used the window power excessively presents plenty of jump scares, and the mystery of the world beyond the window is equally frightening. Yes, the villagers may act irrationally, but there is a reason why fear of death is so common, why people are frightened to move to a different city, to take on a new job – the unknown is an understandable fear, and all of us can act irrationally to avoid it.

Perhaps the scariest part of the manga is its ending. Yoriyuki is spirited away to the unknown, the students resume their lives in their hometowns, and Nanmaru returns to his normal life without using his power, but the villagers restore the crater left by Yoriyuki’s departure almost overnight, and as if they’ve learnt nothing at all, continue their yearly ritual on the mountain. There is a lesson here in the allure of tradition: that sometimes, what makes sense simply isn’t sensible enough, and what is habitual is too comforting to abandon. Sometimes I look at the current state of the world, the shift to conservatism in the face of extreme economic disparity and hardship, and the unwillingness for people even of left-leaning proclivities to vote for non-mainstream, revolutionary parties, and wonder if Marukami Village is closer than we think.

This is an obvious recommend – although I should point out that the artwork is rough at times.

7/10